The rising cost of pharmaceuticals has partly been driven by expensive specialty medications, such as curative gene therapies. This has raised concerns from patients and payers over equitable access, long-term value, and efficiency of healthcare spending.1,2 For high-cost therapies with unclear value, payers are increasingly looking to engage in value-based contracts (VBCs) as a mode of shifting some of the risk associated with the uncertainties to the manufacturer.1,3

Traditional fee-for-service payment models have multiple limitations. They do not consider a drug’s effectiveness, are not fundamentally designed to reward improved patient outcomes and have a revenue model that is volume-based.3 VBCs encompass a broad variety of models and contracting strategies used to determine how much value can be attributed to a drug or health technologies ability to aid in achieving specific goals in a defined patient population.4 Some prominent outcomes utilized in VBCs include utilization rates, endpoints, lab values, adherence, and patient-reported outcomes.4 Often times, VBCs can include a performance-based agreement between payers and manufacturers in which the payment is tied to predetermined outcomes such as clinical or economic endpoints.3

Shifting from the status quo has been a challenging transition for manufacturers and payers as both sides attempt to protect their interests. The development and implementation of VBCs are complicated by divergent perceptions about the value of a product, the willingness to assume risk, the cost of implementation, and disagreements surrounding contract design and contractual protections; however, these obstacles can be mitigated through the use of different types of VBC agreements.5 For example, agreements at the population level of a health plan can be used as a strategy to balance the risk sharing between payers and manufacturers since upfront investment is required from both sides.4,5

On July 1, 2022, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) established best practice guidelines to permit flexibility by Medicaid programs to engage and negotiate in specific terms of value-based purchasing (VBP) by giving manufacturers two options for reporting best prices.6 This new rule stipulates that manufacturers that offer a VBP arrangement to all states will repost the best price. Alternatively, for manufacturers that do not offer a VBP arrangement to all states, a single best price should be reported, including rebates and other discounts for entities eligible for the best price.6 This new rule has made it imperative for eligible payers to understand and strategically assess VBCs for them to align with their needs.

To understand the trend toward the use of VBCs, we analyzed over 80 publicly disclosed agreements in the United States from 2009 to 2022. For this post, we included any arrangements that deviated from traditional rebate practices, such as flat per-unit discounts or rebates in exchange for preferential formulary status or exclusivity.

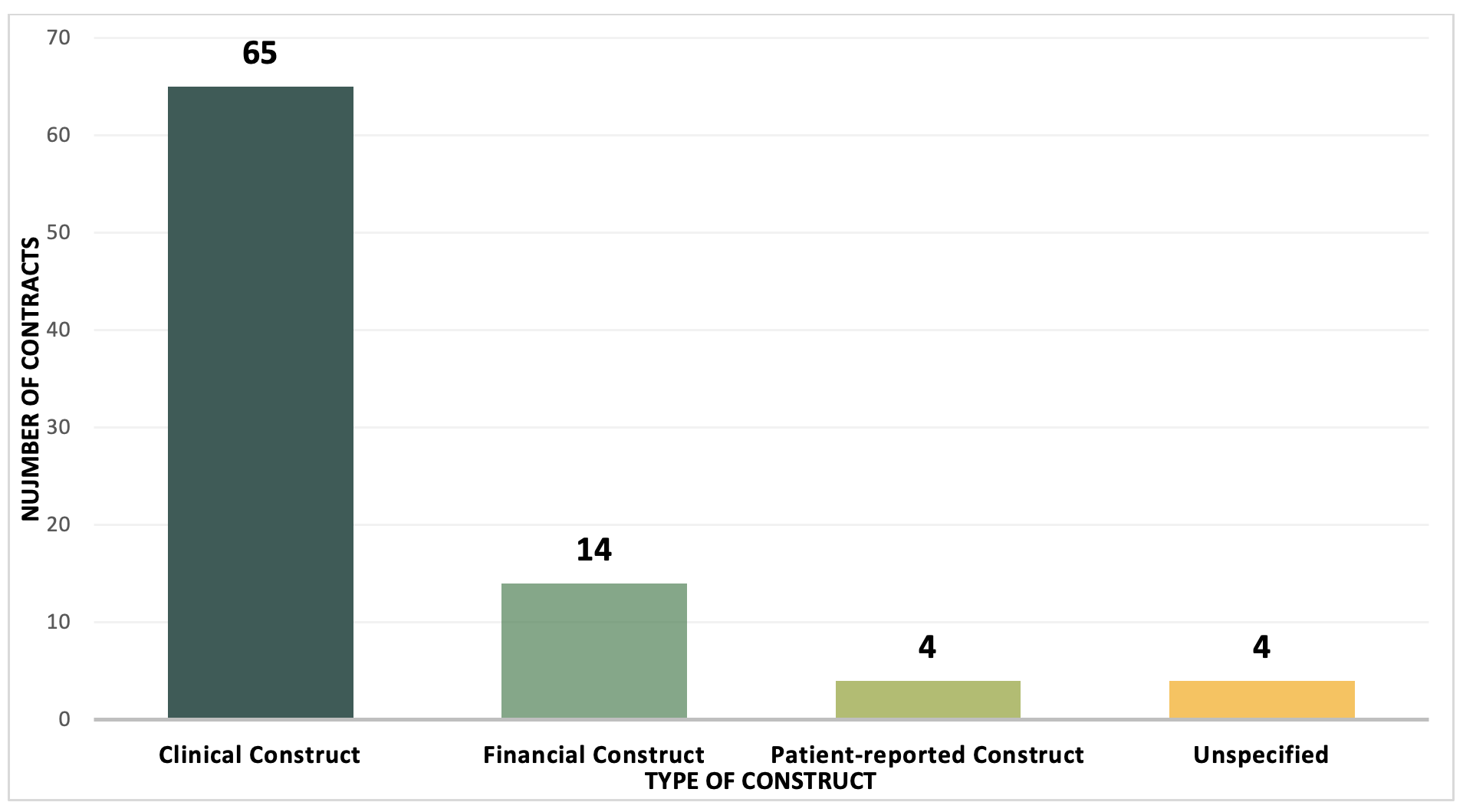

We identified three distinct types of VBC contract constructs from 34 manufacturers across 12 disease states:

- Clinical Construct: Ties the cost of medication to effectiveness in real-world use. Discounts are provided based on measurable factors such as clinical outcomes, patient adherence, abandonment rates, side effects, or reaching a certain dosage threshold.

- Financial Construct: Enhances financial predictability for payers using various methods such as subscription models, prevalence adjustments, or pay-over-time construct.

- Patient-centric Construct: Incorporates the patient’s own report of their symptoms, functionality, and overall well-being. The use of patient-reported outcomes in VBCs allows for a more holistic assessment of the treatment’s effectiveness and patient experience.

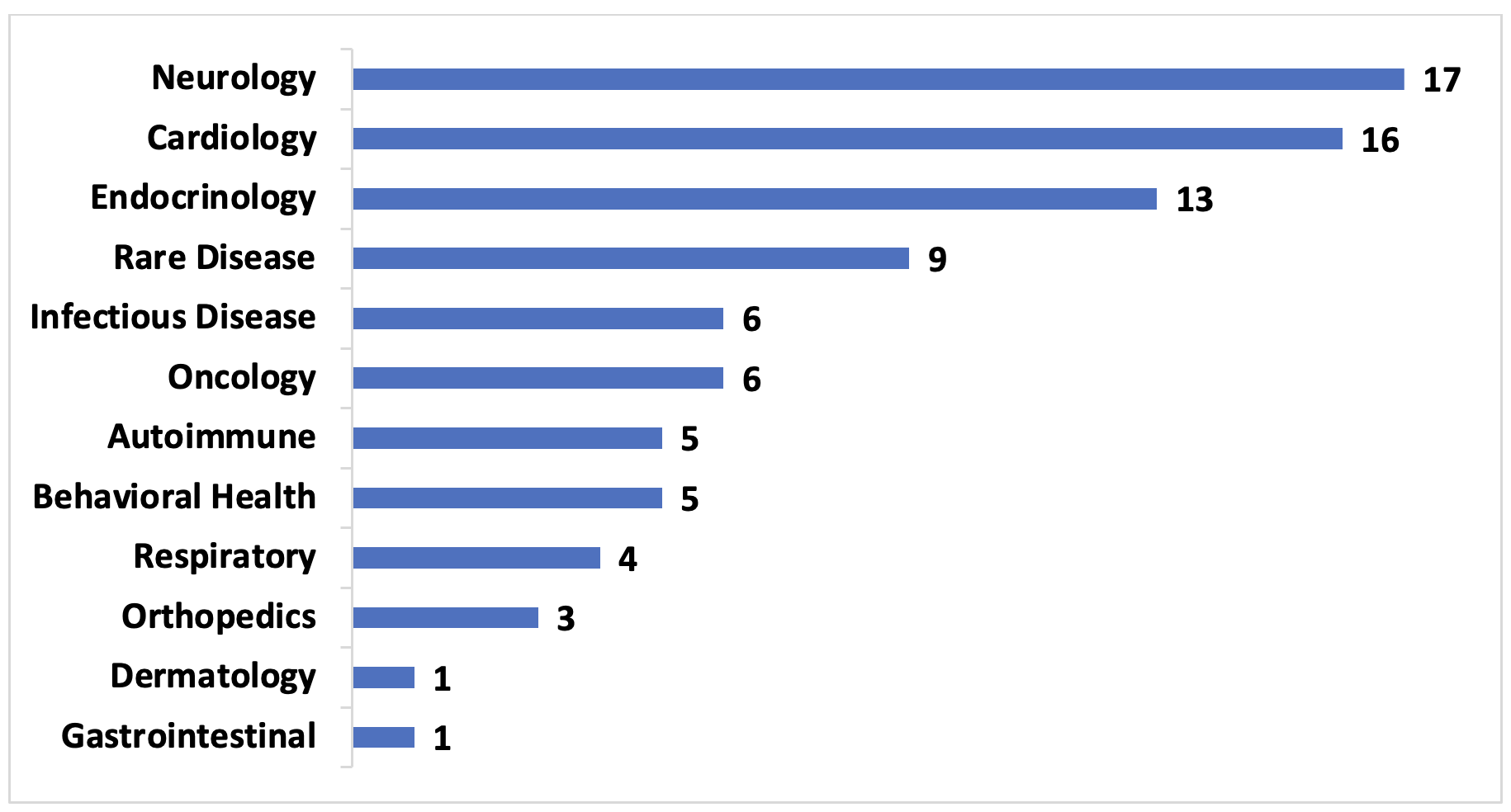

Figure 1. United States VBCs by Therapeutic Area, 2009-2022, number of contracts

Of the publicly disclosed VBCs analyzed, roughly 20% were for drugs that treated neurologic (primarily multiple sclerosis) and cardiology (primarily hyperlipidemia) conditions, and another 25% were for endocrinologic conditions and rare diseases. This distribution is largely driven by the chronic nature of these conditions and the lack of affordable treatment alternatives. As more manufacturers and payers collaborate in these areas, those that only offer traditional arrangements may have difficulty remaining competitive.

Below we describe a few scenarios we’ve identified that make VBCs more appealing to payers than traditional rebate strategies:

- When the product adds significant value compared to the standard of care but is also more expensive. For instance, in the highly genericized market for heart failure: Cigna, Aetna, Harvard Pilgrim Health Care, and Prime Therapeutics participated in VBCs to add Novartis’s Entresto formulary.

- When there is significant market competition among innovative therapies. Praluent and Repatha were two PCSK9 inhibitors approved in 2015 and competed with statins, the established class of cholesterol-lowering drugs. The in-class competition increased the number of VBCs offered to different payers.

- Balancing medical versus pharmacy spend. Biogen entered into VBCs with Express Scripts, Harvard Pilgrim Health Care, Moda Health, and SelectHealth to measure the relapse rate for multiple sclerosis. By decreasing the number of hospital and emergency room visits, this approach may decrease overall healthcare costs, but payers will need to consider the potential for increased prescription costs in the short term.

- Uncertainty around the value of the product. Pear Therapeutics and Prime Therapeutics engaged in VBCs for reSET and reSET-O centered on hospital inpatient stay, overall healthcare cost, and physician product engagement. VBCs enable payers to obtain product experience, lowering ambiguity about therapeutic value, performance, and financial impact.

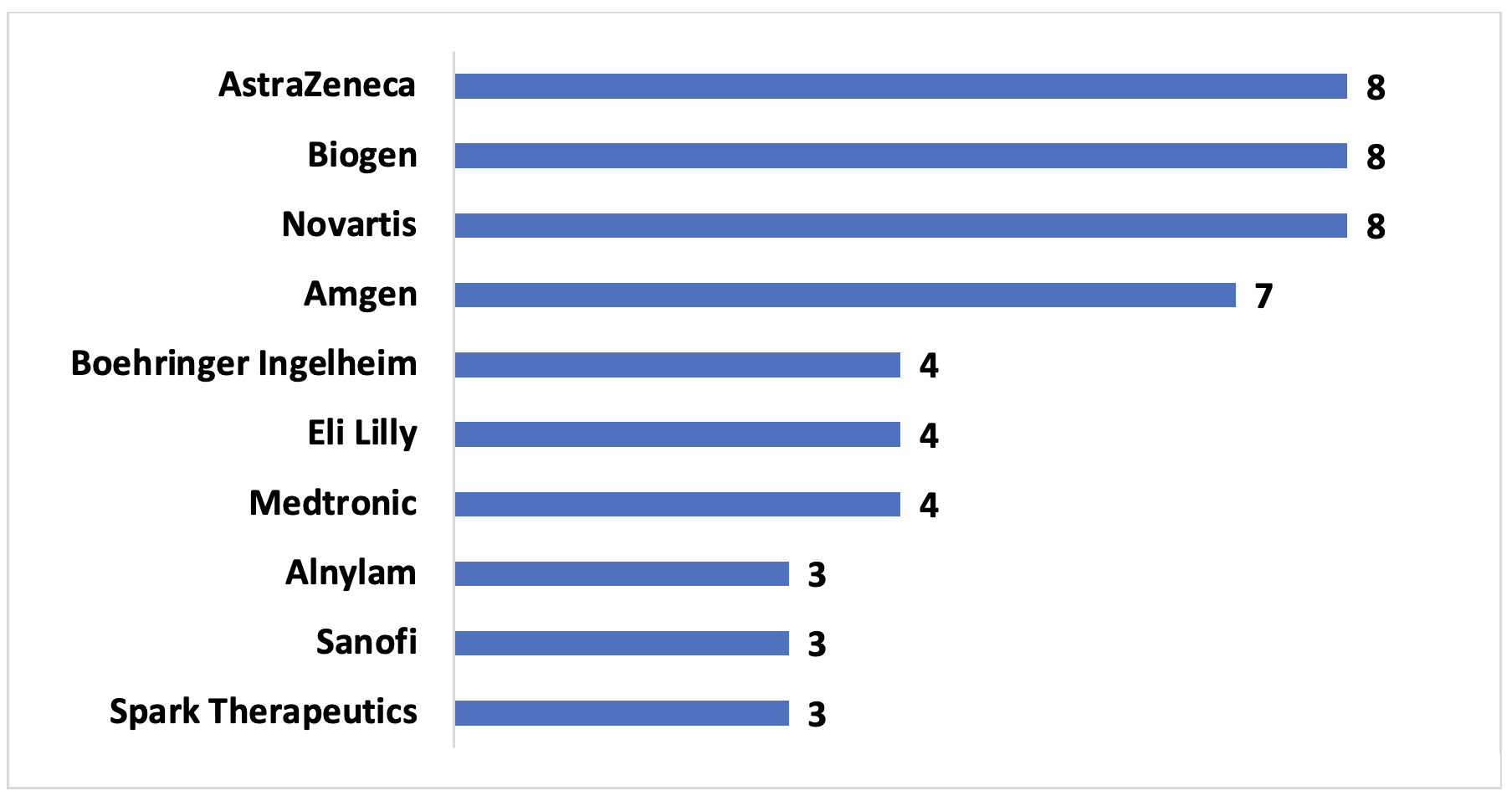

Example 2. US Pharmaceutical manufacturers with three or more VBCs since 2009, with number of contracts

According to our data, pharmaceutical manufacturers with significant market caps and those that focus on rare diseases are more likely to participate in VBCs. Large pharmaceutical manufacturers often have resources and specialized staff that are capable of designing and implementing VBCs. Their broad portfolio also may contribute to a willingness to safeguard public perception. On the other hand, rare disease manufacturers may be more incentivized to use VBCs to promote market access in order to justify their product’s higher price tag. Additionally, VBCs may provide additional data to further understand the disease and the effectiveness of the treatment.

Example 3. Types of VBC Constructs, 2009-2022, number of contracts

A clinical construct based on measurable outcomes is still the most common type of VBCs utilized by manufacturers and payers to align the value of a product. VBCs are most feasible to implement when the treatment being evaluated has a clear target population and a clinical endpoint measurable in claims data. For the treatment of diabetes, Jardiance is a good example, since the patient population can be accurately measured using ICD-10 codes, and clinical outcomes can be captured using claims data.

Manufacturers have long criticized Medicaid Best Price as inhibiting the use of VBCs in the commercial space, as VBCs for a single commercial patient could end up setting the rebate for all Medicaid patients using that drug, regardless of their outcomes. To address this conundrum, CMS’s Multiple Best Price Rule allows the manufacturer to report multiple best prices for VBP arrangements, so long as the manufacturer makes the VBP arrangement available to state Medicaid programs. Despite the rule going into effect for more than six months ago and paving the way for VBCs for Medicaid and commercial payers, no VBCs have been published on the CMS Portal as of January 2023.

VBCs are more complex than traditional arrangements and require more time, resources, and collaboration. VBCs can be difficult to execute unless both payers and manufacturers invest in the necessary capabilities and gain leadership buy-in. While traditional contracting approaches will likely continue to dominate the market, we believe VBCs can be a good complement when conditions are appropriate. To successfully integrate VBCs into their operations, manufacturers and payers should consider investing in innovative analytical tools, processes, and knowledge.

ForHealth Consulting™ at UMass Chan Medical School has a highly experienced, multidisciplinary clinical pharmacy team that understands VBCs and today’s fast-changing healthcare environment. We recognize payers’ and providers’ need to continually assess and improve prescribing and coverage practices. Our mission is to offer innovative options to help clients achieve the highest-quality patient outcomes while ensuring the cost-effectiveness of your pharmacy benefit programs, even as expenses rise and budgets tighten.

Get in contact with us to learn more about how we can do this together.

References:

- Dubois RW, Westrich K and Buelt L. Are value-based arrangements the answer we’ve been waiting for? VALUE HEALTH. 2020 Apr;23(4):418-420.

- Morgan S, Bathula HS, et al. Pricing of pharmaceuticals is becoming a major challenge for health systems. BMJ. 2020;368:14627.

- Kannarkat JT, Good CB and Parekh N. Value-based pharmaceutical contracts: value for whom? VALUE HEALTH. 2020 Feb;23(2):154-156.

- AMCP. Advancing value-based contracting. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2017 Nov;23(11):1096-1102

- Eggbeer B, Sears K, and Homer K. Finding the sweet spot in value-based contracts: with the transition to fee for value accelerating in healthcare markets across the nation, the time is at hand for providers to develop and implement value-based contracts. Healthcare Financial Management Association. 2015 Aug;69(8).

- CMS. Medicaid drug rebate program notice for participating drug manufacturers: technical guidances – value-based purchasing (VBP) arrangements for drug therapies using multiple best prices.